How Much Money Did It Cost To Build Library Of Congress

Coordinates: 38°53′19″N 77°00′17″Due west / 38.88861°Due north 77.00472°W / 38.88861; -77.00472

| Library of Congress | |

|---|---|

| |

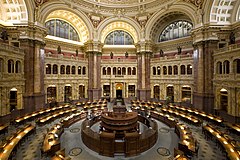

Main reading room | |

| Established | April 24, 1800 |

| Location | Washington, D.C. |

| Drove | |

| Size | 171 meg items[a] |

| Access and use | |

| Circulation | Onsite use only |

| Population served | Congress and nation |

| Other data | |

| Budget | $684.04 million[2] |

| Director | Carla Hayden |

| Staff | 3,105[2] |

| Website | loc |

The Library of Congress (LC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the de facto national library of the United states of america. Information technology is the oldest federal cultural institution in the state. The library is housed in 3 buildings on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C.; it also maintains a conservation centre in Culpeper, Virginia.[3] The library's functions are overseen past the Librarian of Congress, and its buildings are maintained by the Architect of the Capitol. The Library of Congress is i of the largest libraries in the earth.[4] [5] Its "collections are universal, not express by bailiwick, format, or national purlieus, and include research materials from all parts of the world and in more than 450 languages."[3]

Congress moved to Washington, D.C., in 1800 after holding sessions for eleven years in the temporary national capitals in New York City and Philadelphia. In both cities, members of the U.S. Congress had access to the sizable collections of the New York Gild Library and the Library Company of Philadelphia.[6] The pocket-size Congressional Library was housed in the U.s.a. Capitol for most of the 19th century until the early on 1890s.

Well-nigh of the original collection was burnt by the British during the War of 1812, with the library start efforts to restore its drove in 1815. The library purchased Thomas Jefferson's entire personal collection of 6,487 books, and its collection slowly expanded in the post-obit years, although it suffered some other burn down in its Capitol chambers in 1851. This destroyed a large amount of the collection, including many of Jefferson's books. Later on the American Ceremonious War, the importance of the Library of Congress increased with its growth, and in that location was a campaign to purchase replacement copies for volumes that had been burned. The library received the correct of transference of all copyrighted works to deposit two copies of books, maps, illustrations, and diagrams printed in the United States. Information technology too began to build its collections. Its development culminated between 1888 and 1894 with the construction of its own dissever, big library building across the street from the Capitol. Two additional buildings take been constructed nearby to concur collections and provide services, ane in the 1930s and one in the 1970s.

The library'southward primary mission is to research inquiries made by members of Congress, which is carried out through the Congressional Research Service. Information technology besides houses and oversees the United states Copyright Part. The library is open to the public for enquiry, although only high-ranking government officials and library employees may cheque out (i.e., remove from the bounds) books and materials.[7]

History [edit]

1800–1851: Origin and Jefferson's contribution [edit]

James Madison of Virginia is credited with the idea of creating a congressional library, first making such a proffer in 1783.[8] The Library of Congress was after established on April 24, 1800, when President John Adams signed an act of Congress as well providing for the transfer of the seat of regime from Philadelphia to the new upper-case letter city of Washington. Function of the legislation appropriated $five,000 "for the buy of such books as may be necessary for the use of Congress ... and for fitting upwardly a suitable flat for containing them."[9] Books were ordered from London, and the collection consisted of 740 books and three maps, which were housed in the new Usa Capitol.[10]

President Thomas Jefferson played an important role in establishing the construction of the Library of Congress. On January 26, 1802, he signed a nib that allowed the president to appoint the librarian of Congress and establishing a Joint Committee on the Library to regulate and oversee information technology. The new law also extended borrowing privileges to the president and vice president.[11] [12]

In August 1814, after routing an American army at Bladensburg, the British bloodlessly occupied Washington, D.C. In retaliation for the American destruction of Port Dover, the British ordered the destruction of numerous public buildings in the city. British troops burned the Library of Congress, including its collection of iii,000 volumes.[10] These volumes had been held in the Senate wing of the Capitol.[12] [13] One of the few congressional volumes to survive was a government account book of receipts and expenditures for 1810.[14] It was taken as a souvenir by British naval officer Sir George Cockburn, whose family returned it to the United States government in 1940.[15]

Within a month, Thomas Jefferson offered to sell his large personal library[16] [17] [xviii] as a replacement. Congress accepted his offering in January 1815, appropriating $23,950 to purchase his 6,487 books.[10] Some members of the House of Representatives opposed the outright buy, including New Hampshire representative Daniel Webster. He wanted to return "all books of an atheistical, irreligious, and immoral tendency".[xix]

Jefferson had spent 50 years accumulating a wide variety of books in several languages, and on subjects such equally philosophy, history, law, religion, architecture, travel, natural sciences, mathematics, studies of classical Greece and Rome, modern inventions, hot air balloons, music, submarines, fossils, agronomics, and meteorology.[8] He had as well collected books on topics not unremarkably viewed as part of a legislative library, such equally cookbooks. But, he believed that all subjects had a identify in the Library of Congress. He remarked:

I do non know that it contains any branch of science which Congress would wish to exclude from their collection; in that location is, in fact, no subject field to which a Member of Congress may not have occasion to refer.[19]

Jefferson's collection was unique in that it was the working collection of a scholar, not a admirer'due south collection for display. With the addition of his drove, which doubled the size of the original library, the Library of Congress was transformed from a specialist's library to a more than general 1.[xx] His original collection was organized into a scheme based on Francis Salary's system of noesis. Specifically, Jefferson had grouped his books into Retentivity, Reason, and Imagination, and broke them into 44 more subdivisions.[21] The library followed Jefferson's organization scheme until the late 19th century, when librarian Herbert Putnam began work on a more than flexible Library of Congress Classification structure. This now applies to more than than 138 million items.

1851–1865: Weakening [edit]

On December 24, 1851, the largest fire in the library's history destroyed 35,000 books, nigh two–thirds of the library's collection and two-thirds of Jefferson's original transfer. Congress appropriated $168,700 to replace the lost books in 1852 just not to acquire new materials[22] (By 2008, the librarians of Congress had plant replacements for all but 300 of the works that had been documented as being in Jefferson's original collection.[23]) This marked the start of a bourgeois menses in the library'south administration past librarian John Silva Meehan and joint committee chairman James A. Pearce, who restricted the library's activities.[22] Meehan and Pearce's views about a restricted scope for the Library of Congress reflected those shared by members of Congress. While Meehan was librarian, he supported and perpetuated the notion that "the congressional library should play a limited role on the national scene and that its collections, past and big, should emphasize American materials of obvious use to the U.Due south. Congress."[24] In 1859, Congress transferred the library'southward public document distribution activities to the Section of the Interior and its international book exchange program to the Section of State.[25]

During the 1850s, Smithsonian Institution librarian Charles Bury Jewett aggressively tried to develop the Smithsonian every bit the The states' national library. His efforts were blocked by Smithsonian secretary Joseph Henry, who advocated a focus on scientific research and publication.[26] To reinforce his intentions for the Smithsonian, Henry established laboratories, adult a robust concrete sciences library, and started the Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge, the first of many publications intended to disseminate inquiry results.[27] For Henry, the Library of Congress was the obvious option equally the national library. Unable to resolve the conflict, Henry dismissed Jewett in July 1854.

In 1865 the Smithsonian edifice, also called the Castle due to its Norman architectural style, was severely damaged past burn down. This incident presented Henry with an opportunity related to the Smithsonian's non-scientific library. Effectually this fourth dimension, the Library of Congress was making plans to build and relocate to the new Thomas Jefferson Edifice, designed to be fireproof.[28] Authorized past an act of Congress, Henry transferred the Smithsonian's non-scientific library of 40,000 volumes to the Library of Congress in 1866.[29]

President Abraham Lincoln appointed John M. Stephenson every bit librarian of Congress in 1861; the date is regarded as the most political to date.[thirty] Stephenson was a physician and spent equal time serving as librarian and equally a physician in the Union Army. He could manage this division of involvement because he hired Ainsworth Rand Spofford as his assistant.[xxx] Despite his new job, Stephenson focused on the war. 3 weeks into his term as Librarian of Congress, he left Washington, D.C. to serve as a volunteer aide-de-camp at the battles of Chancellorsville and Gettysburg during the American Ceremonious State of war.[30] Stephenson's hiring of Spofford, who directed the library in his absence, may have been his nigh significant achievement.[30]

1865–1897: Spofford's expansion [edit]

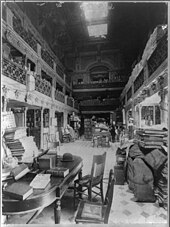

Library of Congress in the Capitol Building in the 1890s

Librarian Ainsworth Rand Spofford, who directed the Library of Congress from 1865 to 1897, built broad bipartisan back up to develop it equally a national library and a legislative resource.[31] [32] He was aided past expansion of the federal government after the war and a favorable political climate. He began comprehensively collecting Americana and American literature, led the construction of a new edifice to house the library, and transformed the librarian of Congress position into ane of force and independence. Between 1865 and 1870, Congress appropriated funds for the construction of the Thomas Jefferson Building, placed all copyright registration and deposit activities nether the library's control, and restored the international book exchange. The library also caused the vast libraries of the Smithsonian and of historian Peter Force, strengthening its scientific and Americana collections significantly. Past 1876, the Library of Congress had 300,000 volumes; information technology was tied with the Boston Public Library as the nation's largest library. It moved from the Capitol edifice to its new headquarters in 1897 with more than 840,000 volumes, 40 percent of which had been caused through copyright eolith.[10]

A year before the library's relocation, the Joint Library Committee held hearings to assess the condition of the library and plan for its time to come growth and possible reorganization. Spofford and six experts sent past the American Library Clan[33] testified that the library should continue its expansion to become a true national library. Based on the hearings, Congress authorized a budget that allowed the library to more than double its staff, from 42 to 108 persons. Senators Justin Morrill of Vermont and Daniel W. Voorhees of Indiana were particularly helpful to gaining this support. The library also established new administrative units for all aspects of the collection. In its bill, Congress strengthened the office of Librarian of Congress: information technology became responsible to govern the library and make staff appointments. As with presidential Chiffonier appointments, the Senate was required to corroborate presidential appointees to the position.[10]

1897–1939: Post-reorganization [edit]

Library of Congress in its new Thomas Jefferson building in 1902

With this back up and the 1897 reorganization, the Library of Congress began to grow and develop more rapidly. Spofford'southward successor John Russell Young overhauled the library's bureaucracy, used his connections equally a former diplomat to acquire more materials from effectually the world, and established the library's first assistance programs for the blind and physically disabled.

Immature's successor Herbert Putnam held the function for twoscore years from 1899 to 1939. Two years after he took office, the library became the first in the Usa to hold i million volumes.[ten] Putnam focused his efforts to make the library more than accessible and useful for the public and for other libraries. He instituted the interlibrary loan service, transforming the Library of Congress into what he referred to as a "library of last resort".[34] Putnam besides expanded library access to "scientific investigators and duly qualified individuals", and began publishing primary sources for the do good of scholars.[ten]

During Putnam'due south tenure, the library broadened the diversity of its acquisitions. In 1903, Putnam persuaded President Theodore Roosevelt to use executive club to transfer the papers of the Founding Fathers from the State Department to the Library of Congress. Putnam expanded foreign acquisitions every bit well, including the 1904 purchase of a four-thousand volume library of Indica, the 1906 purchase of G. V. Yudin's eighty-thousand volume Russian library, the 1908 Schatz collection of early opera librettos, and the early 1930s purchase of the Russian Purple Collection, consisting of 2,600 volumes from the library of the Romanov family on a variety of topics. Collections of Hebraica, Chinese, and Japanese works were as well acquired. On one occasion, Congress initiated an acquisition: in 1929 Congressman Ross Collins (D-Mississippi) gained approval for the library to purchase Otto Vollbehr's collection of incunabula for $1.5 million. This collection included one of iii remaining perfect vellum copies of the Gutenberg Bible.[35] [ten]

Putnam established the Legislative Reference Service (LRS) in 1914 as a separative administrative unit of the library. Based in the Progressive era's philosophy of science to be used to solve issues, and modeled after successful enquiry branches of state legislatures, the LRS would provide informed answers to Congressional inquiry inquiries on almost any topic.

Congress passed in 1925 an deed assuasive the Library of Congress to found a trust fund lath to take donations and endowments, giving the library a role as a patron of the arts. The library received donations and endowments by such prominent wealthy individuals as John D. Rockefeller, James B. Wilbur, and Archer Thousand. Huntington. Gertrude Clarke Whittall donated five Stradivarius violins to the library. Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge's donations paid for a concert hall to be synthetic inside the Library of Congress building and an honorarium established for the Music Division to pay live performers for concerts. A number of chairs and consultantships were established from the donations, the near well-known of which is the Poet Laureate Consultant.[ten]

The library's expansion somewhen filled the library's Main Building, although it used shelving expansions in 1910 and 1927. The library needed to expand into a new structure. Congress acquired nearby country in 1928 and approved construction of the Annex Building (later on known as the John Adams Edifice) in 1930. Although delayed during the Depression years, it was completed in 1938 and opened to the public in 1939.[10]

1939–1987: National versus legislative role [edit]

After Putnam retired in 1939, President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed poet and writer Archibald MacLeish equally his successor. Occupying the post from 1939 to 1944 during the acme of World War II, MacLeish became the most widely known librarian of Congress in the library's history. MacLeish encouraged librarians to oppose totalitarianism on behalf of democracy; dedicated the Due south Reading Room of the Adams Building to Thomas Jefferson, and commissioning artist Ezra Wintertime to pigment four themed murals for the room. He established a "republic alcove" in the Main Reading Room of the Jefferson Building for important documents such every bit the Proclamation of Independence, the Constitution, and The Federalist Papers. The Library of Congress assisted during the war endeavor, ranging from storage of the Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution in Fort Knox for safekeeping, to researching weather information on the Himalayas for Air Force pilots. MacLeish resigned in 1944 when appointed as Assistant Secretarial assistant of Country.

President Harry Truman appointed Luther H. Evans equally librarian of Congress. Evans, who served until 1953, expanded the library's acquisitions, cataloging and bibliographic services. Only he is best known for creating Library of Congress Missions effectually the world. Missions played a diversity of roles in the postwar world: the mission in San Francisco assisted participants in the coming together that established the United Nations, the mission in Europe acquired European publications for the Library of Congress and other American libraries, and the mission in Japan aided in the creation of the National Diet Library.[10]

Adams Building – South Reading Room, with murals by Ezra Winter

Evans' successor Lawrence Quincy Mumford took over in 1953. During his tenure, lasting until 1974, Mumford directed the initiation of construction of the James Madison Memorial Building, the third Library of Congress building on Capitol Hill. Mumford directed the library during a period of increased educational spending by the regime. The library was able to establish new conquering centers abroad, including in Cairo and New Delhi. In 1967, the library began experimenting with book preservation techniques through a Preservation Office. This has adult as the largest library research and conservation try in the United states.

During Mumford's administration, the final major public argue occurred about the Library of Congress'due south part as both a legislative library and a national library. Asked past Joint Library Commission chairman Senator Claiborne Pell (D-RI) to assess operations and make recommendations, Douglas Bryant of Harvard Academy Library proposed a number of institutional reforms. These included expansion of national activities and services and diverse organizational changes, all of which would emphasize the library's national role rather than its legislative role. Bryant suggested changing the name of the Library of Congress, a recommendation rebuked by Mumford as "unspeakable violence to tradition". The debate connected within the library community for some fourth dimension. The Legislative Reorganization Act of 1970 renewed emphasis for the library on its legislative roles, requiring greater focus on research for Congress and congressional committees, and renaming the Legislative Reference Service as the Congressional Research Service.[x]

Later Mumford retired in 1974, President Gerald Ford appointed historian Daniel J. Boorstin as librarian. Boorstin's first claiming was to manage the relocation of some sections to the new Madison Building, which took place between 1980 and 1982. With this accomplished, Boorstin focused on other areas of library administration, such equally acquisitions and collections. Taking advantage of steady budgetary growth, from $116 million in 1975 to over $250 million by 1987, Boorstin enhanced institutional and staff ties with scholars, authors, publishers, cultural leaders, and the business community. His activities changed the post of librarian of Congress so that by the time he retired in 1987, The New York Times called this office "perhaps the leading intellectual public position in the nation".

1987–present: Digitization and programs [edit]

President Ronald Reagan nominated historian James H. Billington as the 13th librarian of Congress in 1987, and the U.S. Senate unanimously confirmed the appointment.[37] Nether Billington'south leadership, the library doubled the size of its analog collections from 85.5 meg items in 1987 to more than than 160 meg items in 2022. At the same time, it established new programs and employed new technologies to "get the champagne out of the canteen". These included:

- American Memory created in 1990, which became the National Digital Library in 1994. It provides free access online to digitized American history and culture resource, including main sources, with curatorial explanations to support use in K-12 teaching.[38]

- Thomas.gov website launched in 1994 to provide free public access to U.South. federal legislative information with ongoing updates; and Congress.gov website to provide a country-of-the-fine art framework for both Congress and the public in 2022;[39]

- National Volume Festival, founded in 2000 with Kickoff Lady Laura Bush,[40] has attracted more than 1000 authors and a one thousand thousand guests to the National Mall and the Washington Convention Centre to celebrate reading. With a major gift from David Rubenstein in 2022, the library established the Library of Congress Literacy Awards to recognize and back up achievements in improving literacy in the U.S. and abroad;[41]

- Kluge Middle, started with a grant of $sixty 1000000 from John W. Kluge in 2000, this brings international scholars and researchers to utilise library resources and to interact with policymakers and the public. It hosts public lectures and scholarly events, provides endowed Kluge fellowships, and awards the Kluge Prize for the Study of Humanity (now worth $one.five million), the get-go Nobel-level international prize for lifetime achievement in the humanities and social sciences (subjects not included in the Nobel awards);[42]

- Open World Leadership Center, established in 2000, by 2022 this program administered 23,000 professional person exchanges for emerging mail service-Soviet leaders in Russian federation, Ukraine, and other successor states of the onetime USSR. Open up World began equally a Library of Congress projection, and later was established as an independent agency in the legislative branch.[43]

- Veterans History Projection, congressionally mandated in 2000 to collect, preserve, and brand accessible the personal accounts of American state of war veterans from WWI to the nowadays twenty-four hour period;[44]

- National Audio-Visual Conservation Center opened in 2007 at a 45-acre site in Culpeper, Virginia, established with a gift of more than than $150 million by the Packard Humanities Constitute, and $82.1 million in boosted support from Congress.

Since 1988, the library has administered the National Motion-picture show Preservation Board. Established by congressional mandate, it selects American films annually for preservation and inclusion in the new National Registry, a collection of American films. The library has fabricated these available on the Internet for gratuitous streaming.[45] Past 2022, the librarian had named 650 films to the registry.[46] The films in the collection date from the earliest to ones produced more than ten years agone; they are selected from nominations submitted to the board. Farther programs included:

- Gershwin Prize for Popular Song,[47] was launched in 2007 to laurels the work of an creative person whose career reflects lifetime achievement in song composition. Winners have included Paul Simon, Stevie Wonder, Paul McCartney, Burt Bacharach and Hal David, Carole King, Baton Joel, and Willie Nelson, as of 2022. The library also launched the Living Legend Awards in 2000 to honor artists, activists, filmmakers, and others who take contributed to America'due south various cultural, scientific, and social heritage;

- Fiction Prize (now the Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction) was started in 2008 to recognize distinguished lifetime achievement in the writing of fiction.[48]

- World Digital Library, established in clan with UNESCO and 181 partners in 81 countries in 2009, makes copies of professionally curated primary materials of the world'southward varied cultures freely bachelor online in multiple languages.[49]

- National Jukebox, launched in 2022, provides streaming free online access to more than 10,000 out-of-print music and spoken word recordings.[50]

- BARD was started in 2022; information technology is a digital, talking books mobile app for braille and audio reading downloads, in partnership with the library's National Library Service for the blind and physically handicapped. Information technology enables free downloads of sound and braille books to mobile devices via the Apple tree App Store.[51]

During Billington'south tenure, the library acquired General Lafayette's papers in 1996 from a castle at La Grange, France; they had previously been inaccessible. Information technology also acquired the only copy of the 1507 Waldseemüller globe map ("America's nascency certificate") in 2003; information technology is on permanent display in the library'south Thomas Jefferson Building. Using privately raised funds, the Library of Congress has created a reconstruction of Thomas Jefferson's original library. This has been on permanent brandish in the Jefferson building since 2008.[52]

Nether Billington, public spaces of the Jefferson Building were enlarged and technologically enhanced to serve as a national exhibition venue. It has hosted more than than 100 exhibitions.[53] These included exhibits on the Vatican Library and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, several on the Civil State of war and Lincoln, on African-American culture, on Religion and the founding of the American Republic, the Early Americas (the Kislak Collection became a permanent display), on the global celebration commemorating the 800th anniversary of the Magna Carta, and on early on American printing, featuring the Rubenstein Bay Psalm Volume. Onsite access to the Library of Congress has been increased. Billington gained an clandestine connectedness between the new U.South. Capitol Visitors Center and the library in 2008 in gild to increase both congressional usage and public tours of the library's Thomas Jefferson Building.[37]

In 2001, the library began a mass deacidification plan, in order to extend the lifespan of most 4 million volumes and 12 million manuscript sheets. Since 2002, new collection storage modules at Fort Meade take preserved and made accessible more than than 4 million items from the library's analog collections.

Billington established the Library Collections Security Oversight Committee in 1992 to improve protection of collections, and besides the Library of Congress Congressional Conclave in 2008 to describe attention to the library'south curators and collections. He created the library's commencement Young Readers Center in the Jefferson Edifice in 2009, and the first large-scale summertime intern (Inferior Fellows) program for university students in 1991.[54] Under Billington, the library sponsored the Gateway to Knowledge in 2022–2011, a mobile exhibition to 90 sites, roofing all states east of the Mississippi, in a specially designed 18-cycle truck. This increased public access to library collections off-site, particularly for rural populations, and helped raise awareness of what was as well available online.[55]

Billington raised more than than half a billion dollars of private support to supplement Congressional appropriations for library collections, programs, and digital outreach. These private funds helped the library to continue its growth and outreach in the face of a 30% subtract in staffing, caused mainly past legislative appropriations cutbacks. He created the library's offset evolution office for private fundraising in 1987. In 1990, he established the James Madison Quango, the library's first national private sector donor-support grouping. In 1987, Billington too asked the GAO to behave the showtime library-wide audit. He created the kickoff Office of the Inspector Full general at the library to provide regular, contained reviews of library operations. This precedent has resulted in regular annual fiscal audits at the library; it has received unmodified ("clean") opinions from 1995 onward.[37]

In Apr 2022, the library announced plans to archive all public communication on Twitter, including all communication since Twitter's launch in March 2006.[56] As of 2022[update], the Twitter archive remains unfinished.[57]

Before retiring in 2022, later 28 years of service, Billington had come "under pressure" equally librarian of Congress.[58] This followed a Government Accountability Function (GAO) report that described a "work environment lacking central oversight" and faulted Billington for "ignoring repeated calls to hire a primary information officer, as required by law."[59]

When Billington appear his plans to retire in 2022, commentator George Weigel described the Library of Congress as "one of the terminal refuges in Washington of serious bipartisanship and calm, considered conversation," and "one of the world's greatest cultural centers."[lx]

Carla Hayden was sworn in every bit the 14th librarian of Congress on September 14, 2022, the commencement adult female and the first African American to concur the position.[61] [62]

In 2022, the library announced the Librarian-in-Residence program, which aims to support the future generation of librarians past giving them the opportunity to gain piece of work experience in five unlike areas of librarianship including: Acquisitions/Collection Evolution, Cataloging/Metadata, and Collection Preservation.[63]

On January 6, 2022, at one:11 PM EST, the Library's Madison Building and the Cannon House Role Building were the first buildings in the Capitol Complex to be ordered to evacuate as rioters breached security perimeters before storming the Capitol edifice.[64] [65] [66] Carla Hayden clarified 2 days later that rioters did not breach whatsoever of Library's buildings or collections and all staff members were safely evacuated.[67]

Holdings [edit]

Thomas Jefferson Edifice the library's main edifice

Ceiling of the Cracking Hall

The collections of the Library of Congress include more than 32 one thousand thousand catalogued books and other print materials in 470 languages; more than 61 million manuscripts; the largest rare book drove[68] in North America, including the rough typhoon of the Declaration of Independence, a Gutenberg Bible (originating from the Saint Blaise Abbey, Black Forest—one of merely three perfect vellum copies known to be);[69] [seventy] [71] over 1 million U.Southward. government publications; 1 million issues of world newspapers spanning the past three centuries; 33,000 spring newspaper volumes; 500,000 microfilm reels; U.S. and strange comic books—over 12,000 titles in all, totaling more than 140,000 issues;[72] films; 5.3 one thousand thousand maps; 6 one thousand thousand works of canvass music; 3 million audio recordings; more than 14.vii million prints and photographic images including fine and popular art pieces and architectural drawings;[73] the Betts Stradivarius; and the Cassavetti Stradivarius.

The library adult a system of book nomenclature called Library of Congress Classification (LCC), which is used past virtually The states research and university libraries.

The library serves equally a legal repository for copyright protection and copyright registration, and as the base for the United States Copyright Office. Regardless of whether they annals their copyright, all publishers are required to submit two complete copies of their published works to the library—this requirement is known equally mandatory eolith.[74] Nearly 15,000 new items published in the U.Due south. arrive every business day at the library. Contrary to popular belief, however, the library does non retain all of these works in its permanent collection, although information technology does add together an average of 12,000 items per day.[3] Rejected items are used in trades with other libraries around the globe, distributed to federal agencies, or donated to schools, communities, and other organizations within the Usa.[three] Equally is true of many similar libraries, the Library of Congress retains copies of every publication in the English language that is deemed significant.

The Library of Congress states that its collection fills about 838 miles (1,349 km) of bookshelves,[5] while the British Library reports nearly 388 miles (624 km) of shelves.[75] The Library of Congress holds more than than 167 million items with more than 39 meg books and other print materials,[5] against approximately 150 meg items with 25 million books for the British Library.[75] A 2000 study by information scientists Peter Lyman and Hal Varian suggested that the amount of uncompressed textual data represented past the 26 million books then in the collection was x terabytes.[76]

The library also administers the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, an audio book and braille library program provided to more 766,000 Americans.

Digitization [edit]

The library's showtime digitization project was called "American Memory". Launched in 1990, it initially planned to choose 160 meg objects from its drove to make digitally available on laserdiscs and CDs that would be distributed to schools and libraries. After realizing that this program would exist too expensive and inefficient, and with the rise of the Cyberspace, the library decided to instead make digitized material bachelor over the Internet. This project was fabricated official in the National Digital Library Program (NDLP), created in October 1994. By 1999, the NDLP had succeeded in digitizing over 5 million objects and had a budget of $12 million. The library has kept the "American Memory" name for its public domain website, which today contains 15 million digital objects, comprising over seven petabytes.[77]

American Memory is a source for public domain prototype resources, besides as audio, video, and archived Web content. Nearly all of the lists of holdings, the catalogs of the library, can be consulted directly on its website. Librarians all over the world consult these catalogs, through the Web or through other media better suited to their needs, when they need to catalog for their collection a volume published in the United States. They use the Library of Congress Control Number to brand sure of the exact identity of the book. Digital images are likewise available at Snapshots of the Past, which provides archival prints.[78]

The library has a budget of $6–8 million each year for digitization, meaning that not all works can exist digitized. It makes determinations about what objects to prioritize based on what is particularly important to Congress or potentially interesting for the public. The 15 one thousand thousand digitized items stand for less than x% of the library'southward total 160-million item collection.

The library has called not to participate in other digital library projects such equally Google Books and the Digital Public Library of America, although it has supported the Cyberspace Archive projection.[77]

THOMAS and Congress.gov projects [edit]

In 1995, the Library of Congress established an online archive of the proceedings of the U.S. Congress, THOMAS. The THOMAS website included the total text of proposed legislation, likewise every bit bill summaries and statuses, Congressional Record text, and the Congressional Record Index. The THOMAS system received major updates in 2005 and 2022. A migration to a more modernized Web system, Congress.gov, began in 2022, and the THOMAS system was retired in 2022.[79] Congress.gov is a joint projection of the Library of Congress, the House, the Senate and the Authorities Publishing Office.[80]

Library of Congress buildings [edit]

The Library of Congress is physically housed in iii buildings on Capitol Loma and a conservation center in rural Virginia. The library's Capitol Hill buildings are all continued by underground passageways, and then that a library user need pass through security merely once in a single visit. The library besides has off-site storage facilities for less commonly requested materials.

Thomas Jefferson Edifice [edit]

The Thomas Jefferson Building is located betwixt Independence Artery and East Capitol Street on Start Street SE. It first opened in 1897 as the main building of the library and is the oldest of the three buildings. Known originally every bit the Library of Congress Building or Main Building, it took its present name on June xiii, 1980.[81]

John Adams Building [edit]

The John Adams Building is located between Independence Avenue and East Capitol Street on second Street SE, the cake adjacent to the Jefferson Building. The building was originally known as The Annex to the Main Building, which had run out of space. It opened its doors to the public on Jan 3, 1939.[82] Initially, it also housed the U.S. Copyright Part which moved to the Madison building in the 1970s.

James Madison Memorial Edifice [edit]

The James Madison Memorial Building is located between Commencement and Second Streets on Independence Avenue SE. The building was constructed from 1971 to 1976, and serves as the official memorial to President James Madison.[83]

The Madison Edifice is besides domicile to the U.Southward. Copyright Office and to the Mary Pickford Theater, the "motility motion-picture show and television reading room" of the Library of Congress. The theater hosts regular free screenings of archetype and contemporary movies and television shows.[84]

Packard Campus for Audio-Visual Conservation [edit]

The Packard Campus for Audio-visual Conservation is the Library of Congress's newest building, opened in 2007 and located in Culpeper, Virginia.[85] It was synthetic out of a former Federal Reserve storage center and Cold War bunker. The campus is designed to act as a single site to shop all of the library's pic, television, and audio collections. It is named to honor David Woodley Packard, whose Packard Humanities Institute oversaw the design and construction of the facility. The centerpiece of the circuitous is a reproduction Art Deco cinema that presents costless moving-picture show screenings to the public on a semi-weekly basis.[86]

Digital Millennium Copyright Human activity [edit]

The Library of Congress, through both the librarian of Congress and the register of copyrights, is responsible for authorizing exceptions to Section 1201 of Championship 17 of the United States Code as part of the Digital Millennium Copyright Human action. This procedure is done every iii years, with the register receiving proposals from the public and interim as an advisor to the librarian, who bug a ruling on what is exempt. Later three years have passed, the ruling is no longer valid and a new ruling on exemptions must be made.[87] [88]

Access [edit]

The library is open up for academic inquiry to anyone with a Reader Identification Card. I may not remove library items from the reading rooms or the library buildings. Nigh of the library's general collection of books and journals are in the closed stacks of the Jefferson and Adams Buildings; specialized collections of books and other materials are in closed stacks in all iii primary library buildings, or are stored off-site. Access to the closed stacks is not permitted nether whatsoever circumstances, except to authorized library staff, and occasionally, to dignitaries. Merely the reading room reference collections are on open up shelves.[89]

Since 1902, American libraries have been able to request books and other items through interlibrary loan from the Library of Congress if these items are not readily available elsewhere. Through this system, the Library of Congress has served as a "library of last resort", according to former Librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam.[34] The Library of Congress lends books to other libraries with the stipulation that they be used merely inside the borrowing library.[xc]

Standards [edit]

In addition to its library services, the Library of Congress is also actively involved in various standard activities in areas related to bibliographical and search and call up standards. Areas of work include MARC standards, Metadata Encoding and Manual Standard (METS), Metadata Object Description Schema (MODS), Z39.fifty and Search/Recollect Spider web Service (SRW), and Search/Recollect via URL (SRU).[91]

The Law Library of Congress seeks to further legal scholarship by providing opportunities for scholars and practitioners to comport significant legal inquiry. Individuals are invited to utilize for projects which would further the multi-faceted mission of the police force library in serving the U.South. Congress, other governmental agencies, and the public.[92]

Annual events [edit]

- Fellows in American Letters of the Library of Congress

- Gershwin Prize for Popular Song

- Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction

- Founder'due south Day Celebration

- National Book Festival

- By and large Lost Film Identification Workshop

Notable personnel [edit]

- Henriette Avram: Adult the MARC format (Machine Readable Cataloging), the international data standard for bibliographic and holdings information in libraries.

- John Y. Cole: founder of the Center for the Book and first historian of the Library of Congress.

- Cecil Hobbs: American scholar of Southeast Asian history, head of the Southern asia Section of the Orientalia (now Asian) Partition of the Library of Congress, and a major correspondent to scholarship on Asia and the development of South E Asian coverage in American library collections[93]

- Julius C. Jefferson Jr., head of the Congressional Research Service, president of the American Library Clan (2020–2021), president of the Freedom to Read Foundation (2013–2016).

See also [edit]

- Documents Expediting Project

- Federal Inquiry Sectionalization

- Feleky Collection

- Law Library of Congress

- Library of Congress Classification

- Library of Congress Country Studies

- Library of Congress Living Legend

- Library of Congress Subject Headings

- Minerva Initiative

- National Digital Library Program (NDLP)

- National Moving-picture show Registry

- National Recording Registry

- National Athenaeum and Records Assistants

- United States Senate Library

Notes [edit]

- ^ The collection includes: 25 million catalogued books, 15.5 million other print items, 4.2 one thousand thousand recordings, 74.five 1000000 manuscripts, 5.six million maps, and viii.ii million sheet music pieces.[1]

References [edit]

- ^ "Twelvemonth 2022 at a Glance". Library of Congress. 2022. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ a b "2017 Annual Study of the Librarian of Congress" (PDF). Library of Congress. Retrieved November 27, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Fascinating Facts". Library of Congress. Retrieved April 25, 2022.

- ^ "Library of Congress". Encyclopedia Britannica . Retrieved September iii, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Fascinating Facts – Statistics". The Library of Congress . Retrieved Feb 16, 2022.

- ^ "History of the Library of Congress". Library of Congress . Retrieved Oct 20, 2022.

- ^ "FY 2022–2023 Strategic Plan of the Library of Congress". Library of Congress. Library of Congress. Retrieved Oct 20, 2022.

- ^ a b Murray, Stuart. The Library: An Illustrated History (New York, Skyhouse Publishing, 2022): 155.

- ^ two Stat. 55

- ^ a b c d eastward f k h i j k 50 "Jefferson's Legacy: A Brief History of the Library of Congress". Library of Congress. March half dozen, 2006. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

- ^ 2 Stat. 128

- ^ a b Murray, Stuart P. (2009). The library: an illustrated history. New York, NY: Skyhorse Pub. pp. 158. ISBN9781602397064.

- ^ Greenpan, Jesse (August 22, 2022). "The British Burn down Washington, D.C., 200 Years Ago". History.com . Retrieved Jan 8, 2022.

- ^ Murray, Stuart (2009). The Library An Illustrated History. Chicago, Illinois: Skyhorse Publishing. p. 159.

- ^ Murray, Stuart (2009). The library : an illustrated history . New York, NY: Skyhorse Pub. ISBN978-ane-60239-706-four.

- ^ "Thomas Jefferson's personal library, at LibraryThing, based on scholarship". LibraryThing. Retrieved Nov iv, 2022.

- ^ LibraryThing profile page for Thomas Jefferson'south library, summarizing contents and indicating sources

- ^ "Jefferson's Library". Library of Congress. April 24, 2000.

- ^ a b Murray, Stuart P. (2009). The library : an illustrated history. Chicago: Skyhorse Pub. pp. 162. ISBN9781602397064.

- ^ Murray, Stuart A.P. The Library: An Illustrated History. Skyhorse Publishing, 2022. 9781616084530, pp. 161

- ^ Murray, Stuart (2009). The Library: An Illustrated History. New York: Skyhorse Publishing. p. 162. ISBN978-1-60239-706-4.

- ^ a b Cole, J.Y. (1993). Jefferson's Legacy: a brief history of the Library of Congress. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. p. xiv.

- ^ Fineberg, Gail (June 2007). "Thomas Jefferson's Library". The Gazette. Library of Congress. 67 (six). Retrieved Jan 4, 2022.

- ^ Cole, J.Y. (2005). "The Library of Congress Becomes a World Leader, 1815–2005". Libraries & Civilisation. 40 (3): 386. doi:ten.1353/lac.2005.0046. S2CID 142764409.

- ^ Interior Library (August 4, 2022). "History of the Interior Library". U.S. Department for the Interior . Retrieved April 30, 2022.

- ^ Smithsonian Establishment (1904). An Account Of The Smithsonian: Its Origin, History, Objects and Achievements. Washington, D.C. p. 12.

- ^ Mearns, D.C. (1946). The Story Upwardly to Now: The Library of Congress, 1800–1946. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. p. 100.

- ^ Library of Congress. "Almanac Written report of the Librarian of Congress 1866" (PDF). U.Due south. Copyright Role . Retrieved April 30, 2022.

- ^ Gwinn, Nancy. "History". Smithsonian Libraries . Retrieved April 30, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Library of Congress. "John One thousand Stephenson". John 1000 Stephenson – Previous Librarians of Congress . Retrieved April 30, 2022.

- ^ Aikin, Jane (2010). "Histories of the Library of Congress". Libraries & the Cultural Record. 45 (ane): eleven–12. ISSN 1932-4855. JSTOR 20720636.

- ^ Weeks, Linton (December thirteen, 1999). "A Bicentennial for the Books". The Washington Mail service . Retrieved October 3, 2022.

- ^ These included future Librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam and Melvil Dewey of the New York State Library.

- ^ a b "Interlibrary Loan (Collections Access, Management and Loan Partitioning, Library of Congress)". Library of Congress website. October 25, 2007. Retrieved December four, 2007.

- ^ Snapp, Elizabeth (April 1975). "The Acquisition of the Vollbehr Collection of Incunabula for the Library of Congress". The Journal of Library History. University of Texas Press. 10 (two): 152–161. JSTOR 25540624. (restricted access)

- ^ Cole, John Y. "The James Madison Building (On These Walls: Inscriptions and Quotations in the Buildings of the Library of Congress, by John Y. Cole)". world wide web.loc.gov . Retrieved Feb 20, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Cardinal Milestones of James H. Billington's Tenure | News Releases – Library of Congress". Loc.gov . Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ "American Memory from the Library of Congress – Home Page". Memory.loc.gov . Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ "Congress.gov | Library of Congress". www.congress.gov . Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ Oder, Norman. "Outset Lady Launches Book Festival." Library Journal 126, no. fourteen (2001): 17

- ^ "2015 Book Festival | National Book Festival – Library of Congress". Loc.gov . Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ "The John W. Kluge Center – Library of Congress". Loc.gov . Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ "Founding Chairman | OpenWorld". www.openworld.gov. Archived from the original on September v, 2022. Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ "Veterans History Projection (Library of Congress)". Loc.gov . Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ Dargis, Manohla, Film Treasures, Streaming Courtesy of the Library of Congress, New York Times, April 3, 2022 with links to videos and collections, and on April 4, 2022, Section C, Page 1, New York edition with the headline: An Online Trove of Picture Treasures

- ^ "Inside the Nuclear Bunker Where America Preserves Its Motion-picture show History". Wired . Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ "Gershwin Prize". Library of Congress . Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ "Fiction Prize". Library of Congress . Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ "Groundwork – Earth Digital Library". www.wdl.org . Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ "National Jukebox LOC.gov". Loc.gov . Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ "NLS Abode". Loc.gov . Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ "Thomas Jefferson'due south Library | Exhibitions – Library of Congress". loc.gov. Apr eleven, 2008. Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ "All Exhibitions – Exhibitions (Library of Congress)". Loc.gov . Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ "2015 Junior Fellows Summer Intern Plan Home (Library of Congress)". Loc.gov . Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ "Gateway to Knowledge – Educational Resources – Library of Congress". Loc.gov . Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ Grier, Peter (April 16, 2022). "Twitter hits Library of Congress: Would Founding Fathers tweet?". Christian Science Monitor . Retrieved January four, 2022.

- ^ Zimmer, Michael (2015). "The Twitter Archive at the Library of Congress: Challenges for information practise and information policy". Kickoff Mon. doi:10.5210/fm.v20i7.5619.

- ^ "Librarian of Congress gets a Due Date" by Maria Recio, McClatchy DC, Oct. thirty. 2022

- ^ "America'southward 'national library' is defective in leadership, yet some other study finds" by Peggy McGlone, The Washington Mail service, March 31, 2022.

- ^ "America's Next 'Minister of Civilisation': Don't Politicize the Date". National Review. June 12, 2022. Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ McGlone, Peggy (July 13, 2022). "Carla Hayden confirmed as 14th librarian of Congress". Washingtonpost.com . Retrieved May five, 2022.

- ^ "Carla Hayden to be sworn in on September fourteen – American Libraries Magazine". Americanlibrariesmagazine.org. Archived from the original on May ten, 2022. Retrieved May v, 2022.

- ^ "Librarians-in-Residence -". The Library of Congress . Retrieved November 7, 2022.

- ^ Budryk, Zack; Lillis, Mike; Coleman, Justine (January 6, 2022). "Capitol placed on lockdown, buildings evacuated amidst protests". The Colina . Retrieved January 8, 2022.

- ^ "Timeline: How a Trump mob stormed the US Capitol, forcing Washington into lockdown". U.s. Today. Jan 8, 2022. Retrieved January 8, 2022.

- ^ @sarahnferris (January half dozen, 2022). "WOW Hill staff just got this alert "Madison: EVACUATE. Proceed to your designated assembly surface area. USCP"" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Hayden, Carla (Jan 8, 2022). "Thoughts on this week'due south unrest" (PDF). The Library of Congress Gazette. 32.

- ^ "Rare Book and Special Collections Reading Room (Library of Congress)". Loc.gov . Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ Nga, Brett. "Gutenberg's Bibles— Where to Find Them". ApprovedArticles.com. Archived from the original on July 6, 2008. Retrieved Apr one, 2008.

- ^ "Octavo Editions: Gutenberg Bible". octavo.com. Archived from the original on November 27, 2004.

- ^ "Europe (Library of Congress Rare Books and Special Collections: An Illustrated Guide)". Loc.gov . Retrieved May five, 2022.

- ^ "Comic Volume Collection". The Library of Congress. August 27, 2022. Retrieved Baronial 27, 2022.

- ^ Annual Report of the Librarian of Congress (PDF), Library of Congress, 2009

- ^ "Mandatory Deposit". Copyright.gov. Retrieved Baronial viii, 2006.

- ^ a b "Facts and figures". British Library. Archived from the original on February seven, 2022. Retrieved June thirty, 2022.

- ^ Lyman, Peter; Varian, Hal R. (October 18, 2000). "How Much Information?" (PDF) . Retrieved October xiv, 2022.

- ^ a b Chayka, Kyle (July 14, 2022). "The Library of Concluding Resort". northward+i Magazine. Archived from the original on January nineteen, 2022. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- ^ "About Us". Snapshots of the By. Archived from the original on May 14, 2022. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ David Gewirtz, So long, Thomas.gov: Within the retirement of a classic Web 1.0 application, ZDNet (May iv, 2022).

- ^ Adam Mazmanian, Library of Congress to retire Thomas, Federal Computer Week (April 28, 2022).

- ^ Cole, John (2008). "The Thomas Jefferson Edifice". On These Walls: Inscriptions and Quotations in the Buildings of the Library of Congress. Scala Arts Publishers Inc. ISBN978-1857595451 . Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- ^ Cole, John (2008). "The John Adams Edifice". On These Walls: Inscriptions and Quotations in the Buildings of the Library of Congress. Scala Arts Publishers Inc. ISBN978-1857595451 . Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- ^ Cole, John (2008). "The James Madison Memorial Edifice". On These Walls: Inscriptions and Quotations in the Buildings of the Library of Congress. Scala Arts Publishers Inc. ISBN978-1857595451 . Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- ^ "Mary Pickford Theater Picture show Schedule". Moving Image Research Center. Library of Congress. Retrieved Apr 23, 2022.

- ^ "The Packard Campus – A/5 Conservation (Library of Congress)". Loc.gov . Retrieved May five, 2022.

- ^ "Library of Congress events listing". Loc.gov. Retrieved Nov four, 2022.

- ^ "Section 1201: Exemptions to Prohibition Against Circumvention of Technological Measures Protecting Copyrighted Works". The states Copyright Office. 2022. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- ^ "Statement Regarding White House Response to 1201 Rulemaking" (Printing release). Library of Congress. 2022. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- ^ "Using the Library's Collections (Research and Reference Services, Library of Congress)". www.loc.gov . Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- ^ "Subpage Title (Interlibrary Loan, Library of Congress)". Loc.gov. July 14, 2022. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ "Standards at the Library of Congress". Loc.gov . Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ "Inquiry & Educational Opportunities – Law Library of Congress". Loc.gov . Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ Tsuneishi, Warren (May 1992). "Obituary: Cecil Hobbs (1907–1991)". Periodical of Asian Studies. 51 (2): 472–473. doi:10.1017/s0021911800041607.

- Mearns, David Chambers. The Story Up to At present: The Library Of Congress, 1800–1946 (1947), detailed narrative

Compages [edit]

- Cole, John Y. and Henry Hope Reed. The Library of Congress: The Art and Architecture of the Thomas Jefferson Edifice (1998) excerpt and text search

- Small, Herbert, and Henry Hope Reed. The Library of Congress: Its Architecture and Decoration (1983)

Further reading [edit]

- Aikin, Jane (2010). "Histories of the Library of Congress". Libraries & the Cultural Record. 45 (1): 5–24. doi:x.1353/lac.0.0113. S2CID 161865550.

- Anderson, Gillian B. (1989), "Putting the Feel of the Earth at the Nation's Control: Music at the Library of Congress, 1800-1917", Journal of the American Musicological Society, 42 (ane): 108–49, doi:10.2307/831419, JSTOR 831419

- Bisbort, Alan, and Linda Barrett Osborne. The Nation's Library: The Library of Congress, Washington, D. C. (Library of Congress, 2000)

- Cole, John Immature. Jefferson'due south legacy: a brief history of the Library of Congress (Library of Congress, 1993)

- Cole, John Young. "The library of congress becomes a globe library, 1815–2005." Libraries & culture (2005) forty#3: 385–398. in Projection MUSE

- Cope, R. L. "Management Review of the Library of Congress: The 1996 Booz Allen & Hamilton Report," Australian Academic & Research Libraries (1997) 28#i online

- Ostrowski, Carl. Books, Maps, and Politics: A Cultural History of the Library of Congress, 1783–1861 (2004) online

- Rosenberg, Jane Aiken. The Nation'southward Not bad Library: Herbert Putnam and the Library of Congress, 1899–1939 (University of Illinois Press, 1993)

- Shevlin, Eleanor F.; Lindquist, Eric Due north. (2010). "The Centre for the Volume and the History of the Volume". Libraries & the Cultural Record. 45 (1): 56–69. doi:x.1353/lac.0.0112. S2CID 161311744.

- Tabb, Winston; et al. (2003). "Library of Congress". Encyclopedia of Library and Informatics. 3: 1593–1612.

External links [edit]

- The Library of Congress website

- Library of Congress YouTube channel

- Search the Library of Congress catalog

- Congress.gov, legislative information

- Library Of Congress Meeting Notices and Rule Changes from The Federal Register RSS Feed

- Library of Congress photos on Flickr

- Outdoor sculpture at the Library of Congress

- Works by Library of Congress at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Library of Congress at Internet Archive

- Library of Congress at FamilySearch Research Wiki for genealogists

- . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- C-SPAN's Library of Congress documentary and resources Archived Apr 12, 2022, at the Wayback Motorcar

- The Library of Congress National Library Service (NLS)

- Video: "Library of Congress in 1968 – Figurer Automation"

- Library of Congress Web Archives – search by URL

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Library_of_Congress

Posted by: cruzromem1970.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Much Money Did It Cost To Build Library Of Congress"

Post a Comment